Table of Contents

Introduction

Granular synthesis is a term used to describe anything that processes audio using granulation: the division of sound into tiny microacoustic events, called grains. Grains can be thought of as the molecular “atoms” that make up sound. After a sound is broken into tiny grains, they can then be redistributed and reorganized to form new sounds. Granular synthesis is perceived as a relatively recent development in sound synthesis, but it can also be seen as a reflection of long-standing ideas about the nature of sound.

Chapter 1 History

1.1 Dennis Gabor

Dennis Gabor was first to conceptualize granular synthesis in 1946, in his Theory of Communication.13 Although the notion that a perceived continuous phenomena can be subdivided into particles traces back to Greek philosophers, the modern scientific theory of microsound dates back to Gabor, who applied the concept of an acoustic quantum to the threshold of human hearing. The original intent of his study was to reduce the amount of data required for human audio communication, necessitated by the low band width but rising use of telecommunication in the 1940s.1 Nonetheless, his theories made their way into the world of music composition as the basis for granular synthesis.

1.2 Iannis Xenakis

Iannis Xenakis came across Gabor's research and began to implement these concepts into his music. Xenakis had previously used the idea of “points” of sound in his compositions for orchestra, although it was not until 1959 that Xenakis modified a reel to reel tape recorder to realize true microacoustic granular synthesis. This process involved splicing magnetic tape into tiny segments, rearranging the segments, and taping the new string of segments together.

His first complete work to use granular synthesis techniques was Analogique A et B. Analogique B is the granular synthesis part of Analogique A-B, and is written to be played simultaneously with Analogique A. Analogique B consists of four tracks to be played through 8 speakers around the concert hall. Xenakis states that each grain has a threefold nature: duration, frequency and intensity.

“All sound, even continuous musical variation, is conceived as an assemblage of a large number of elementary sounds adequately disposed in time. In the attack, body, and decline of a complex sound, thousands of pure sounds appear in a more or less short interval of time. We are in a kind of continuum form, say, usual objects of music that are inaudible, but which produce these events on a higher level.”

— Iannis Xenakis

1.3 Curtis Roads

After attending a lecture by Xenakis on this topic, Curtis Roads began experimenting. Roads was the first to realize granular synthesis using a computer in 1975. His first experiments were extremely time consuming, taking weeks to render a one minute mono sound. Roads expanded on the ideas of Xenakis and his research has led to much of the current work based on granular synthesis. Roads has created many granular synthesis computer programs, notably Cloud Generator which is designed to teach users about granular synthesis.

1.4 Barry Truax

Inspired by an article on granular synthesis written by Roads, Barry Truax began developing a method to create granular synthesis in real-time, first realized in 1986 in his work Riverrun. It is based on synthesized grains which are either simple waveforms or FM signals.

“ Curtis Roads had done it in non-real time, heroically, hundreds of hours of calculation time on mainframes, just to get a few seconds of sound. He had done that, but it remained a textbook case. As soon as I started working with it in real time and heard the sound, it was rich, it was appealing to the ear, immediately, even with just sine waves as the grains. Suddenly they came to life. They had a sense of what I now call volume, as opposed to loudness. They had a sense of magnitude, of size, of weight, just like sounds in the environment do. And it’s not I think coincidental that the first piece I did in 1986 called Riverrun which was the first piece realized entirely with real-time granular synthesis. ”

— Barry Truax 2

Chapter 2 Fundamentals

2.1 Anatomy of a Grain

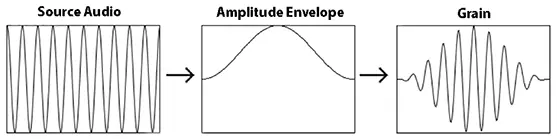

A grain is a short “atom” of sound lasting 1 – 100 ms. Contents of a grain can be sampled audio or synthesized sound waves. From that source, a grain of sound is retrieved. There are three parameters a composer can use to manipulate the contents of a grain: the retrieval point from the source, the duration of the grain, and the playback speed.

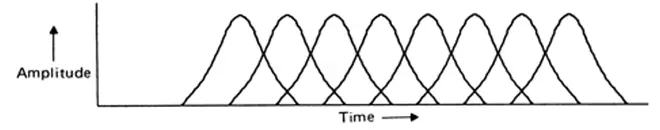

2.2 Grain Window

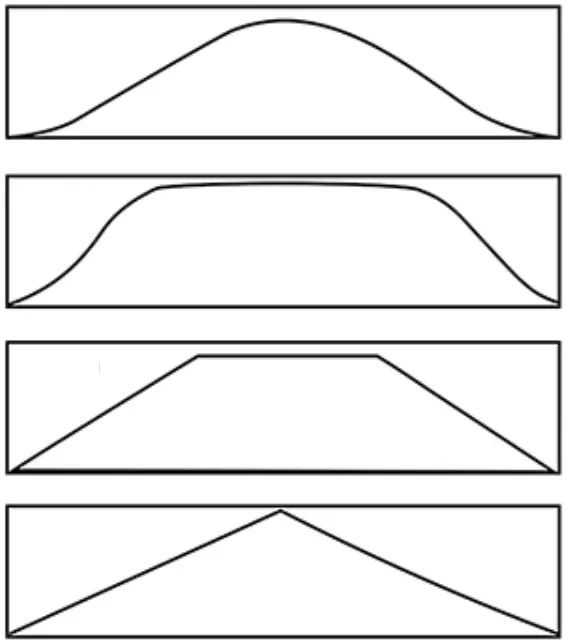

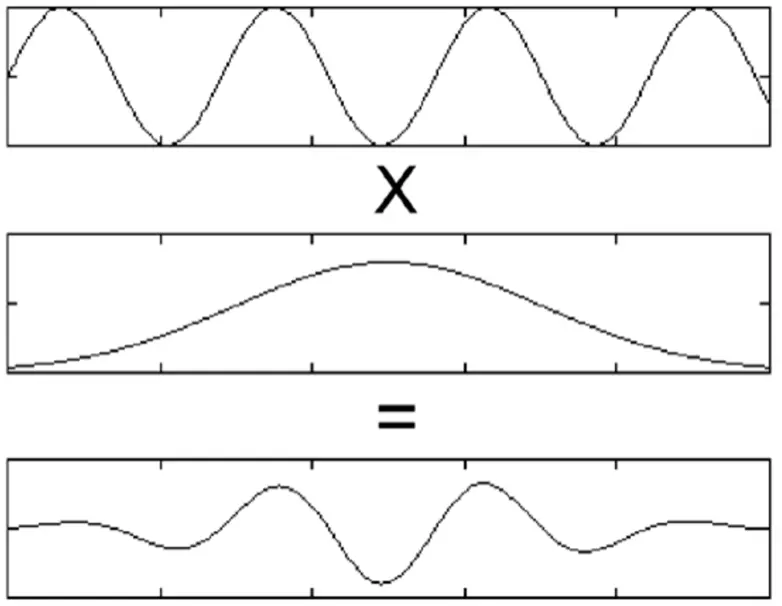

Grains have amplitude fades at their beginning and end, fundamentally to eliminate artifacts in the audio signal. If a waveform is sliced anywhere other than a zero-crossing point, there will be an audible popping sensation. However, since the envelope shape can also have a significant effect on the sound grain, it can be used creatively as a way to shape the sound. The shape of these fades is called the “window” or envelope.

2.2.1 Basic Window Shapes

Basic window shapes have fades at the beginning and end of the envelope. The slope of each fade can be manipulated. The duration of the envelope can also be manipulated.

2.2.2 Complex Shapes

Complex window shapes are rather new to the idea of granular synthesis. They consist of two envelopes. Figure 6 shows an example where the first envelope is a sine type wave. Over the sine wave is placed another wave, any type of linear or exponential wave is adequate.

Chapter 3 Global Organization

Global organization will refer to the organization of grains, specifically how they are arranged in time and space. There are a seemingly infinite number of ways to arrange these acoustic particles. Grains can be played back in different order, overlapping, coming from many speaker locations, really any imaginable configuration. Due to this, granular synthesis requires a massive amount of control data.

“ If n is the number of parameters per grain, and d is the density of grains per second, it takes n times d parameter values to specify one second of sound. Since n is usually greater than ten and d can exceed one thousand, it is clear that a global unit of organization is necessary for practical work. ”

— Curtis Roads 4

The major differences between the various granular techniques are found in these global organizations and algorithms.

3.1 Grain Density

Grain density refers to the number of grains per second. It is frequency in which grains are produced. For example if the density is specified at 200 g/s, then 200 grains will be randomly (or statistically) distributed throughout that second. “A one-second cloud containing twenty 100 ms grains is continuous and opaque, whereas a cloud containing twenty 1 ms grains is sparse and transparent. The difference between these two cases is their fill factor. The fill factor of a cloud is the product of its density and its grain duration in seconds.” 5 For a typical grain duration of 25 ms, we can make the following observations concerning grain density as it crosses perceptual thresholds.

| Grains per second | Perception |

|---|---|

| < 15 | Rhythmic sequences. |

| 15-25 | Fluttering, sensation of rhythm disappears. |

| 25-50 | Grain order disappears. As density increases, we no longer perceive an acceleration of tempo, rather an increase in the flow of grains. |

| 50-100 | Texture band. If the bandwidth is greater than a semitone, we cannot discern individucal frequencies. |

| > 100 | Continuous sound mass. No space between grains. In some cases, resembles reverberation. |

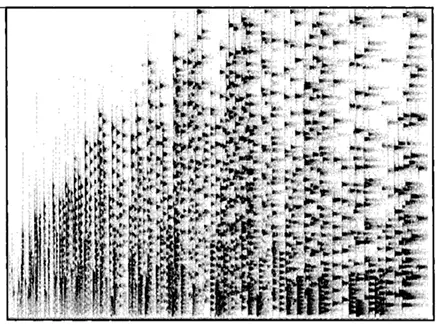

3.1.2 Synchronous

Synchronous granular synthesis implies that the time difference between successive grains, or the hop size — is constant. The spacing between the grains in granular synthesis can radically change the texture that is created. A very low density will produce a rhythmic effect. Once the density reaches a certain level the rhythmic effect will morph into a pitched effect. The frequency produced is the reciprocal of the hop size, which acts as the period of a periodic waveform. The grain duration is so short that the frequency of the waveform within the grain affects the spectrum, but will not change the fundamental pitch of the sound. Roads writes that “synchronous granular synthesis is very closely related to Formant Synthesis”.7

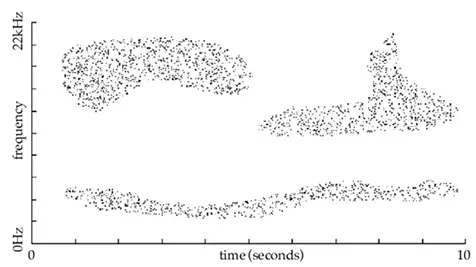

3.1.2 Asynchronous

Asynchronous granular synthesis produces grain clouds by scattering grains in a statistical manner over a specified duration. It abandons the concept of linear streams of grains and instead, disperses grains within regions on the time-frequency plane. The starting time and frequency of each grain can be randomized or controlled through algorithms. Asynchronous granular synthesis typically produces noise textures, rather than pitch. However, it can be perceived often as more of a continuum. Roads writes:

“Some grains may overlap, leaving silences at other points in the cloud. Using 20 ms grains, it takes about 100 grains to cover a one-second cloud. Tiny gaps (less than 50 ms) do not sound as silences, but rather as fluctuations of amplitude.”

By increasing the grain density, we saturate the texture, creating effects that depend on the bandwidth.10

- Narrow bands and high densities generate pitched streams with formant spectra.

- Medium bands (several semitones) and high densities generate turgid colored noise.

- Wide bands (octave or more) and high densities generate massive clouds of sound.

| Grain Duration | Modulation Frequency | Perceived Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 200 usec | 5 KHz | Noisy particulate disintegration |

| 500 usec | 2 KHz | |

| 1 ms | 1 KHz | Loss of pitch |

| 10 ms | 100 Hz | Fluttering, gurgling |

| 50 ms | 20 Hz | Stable pitch formation |

| 100 ms | 10 Hz | |

| 200 ms | 5 Hz | Aperiodic tremolo, jittering |

3.2 Spatialization

Not only can we distribute grains along the time but also the space, the space-time continuum. When grains scatter to a unique locations, the cloud manifests a vivid “three-dimensional spatial morphology”.11 This is evident even in a stereophonic configuration. Spacial location can be manipulated through panning, and spacial depth can be created through reverb amount, volume, and low-pass to create the perception of distance. In Figure 14, the x-axis = panorama, y-axis = pitch modulation, and z-axis = sample reading position.

Chapter 4 Granular Techniques

This chapter will explore practical applications and compositional techniques of granular synthesis.

4.1 Change Speed/Pitch Independently

Granular synthesis allows us to stretch or compress audio, independent of pitch. Before the use of computers, analogue tape decks could be used to speed up or slow down sounds, however this also caused the pitch to shift. Slowing down audio would literally stretch out the frequency of the waveform. This all changed with the advent of computer technology.

The ability to change a sound’s speed without affecting pitch, or vice-versa, is a possible using granular synthesis. With tape, one could stretch a sound, but to maintain the frequency of a wave while stretching it (in theory) would create gaps between the grains. The only way to fill these gaps was to stretch the grains themselves, thus lowering the pitch. By implementing granular synthesis techniques we can alter a sound’s atomic makeup. We can fill the gaps by looping nearby grains.

Figure 17 shows Stockhausen describing this process in 1972, before it was actually possible. Figure 18 shows a modern demonstration of this technique, using Logic Pro X.

4.2 Pulsar Synthesis

Pulsar synthesis is a method of sound synthesis based on the generation of electronic pulses and pitched tones. Pioneers of pulsar synthesis include Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig.12 Pulsar synthesis can produce either rhythms or tones as it crosses perceptual time spans.

“ It is necessary that the strength of the vibrations of the air for very low tones should be extremely greater than for high tones. The increase in strength...is of special consequence in the deepest tones...To discover the limit of the deepest tones it is necessary not only to produce very violent agitations of the air but to give these a simply pendular motion. ”

— Hermann von Helmholtz (1885)

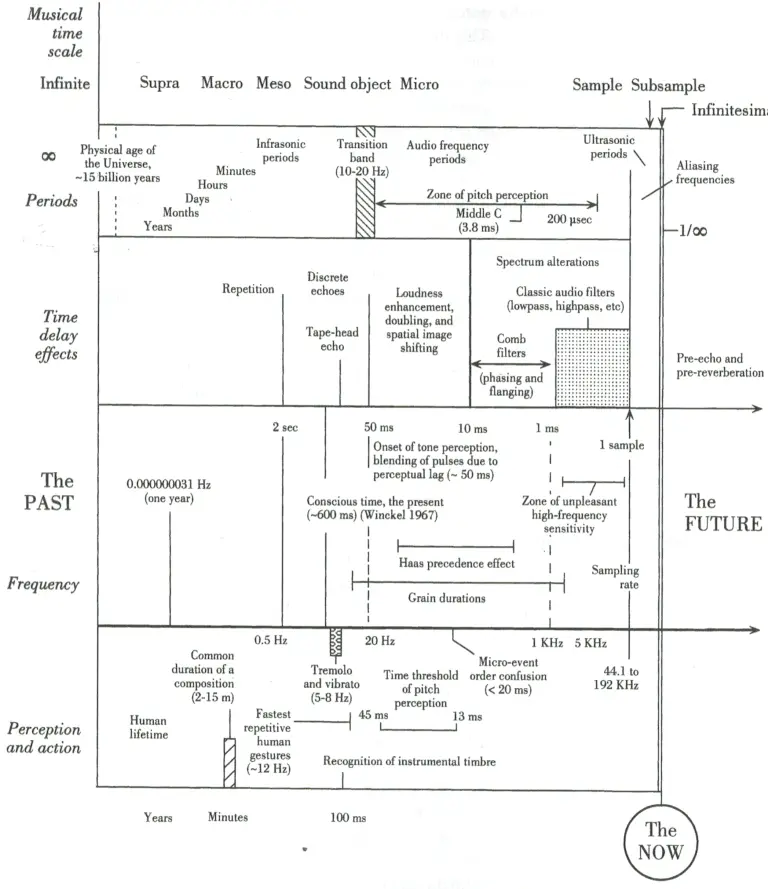

Thus to perceive this transition between time layers, pulses must be strong. Helmholtz observed that a sense of continuity is perceived between 24 to 28 Hz, but that the impression of a definite pitch does not take hold until 40Hz.13 I find this fascinating, and a key ingredient to pulsar synthesis. If music is all about tension and release, this is what makes pulsar synthesis music. Stockhausen formulated a theory of the continuum between rhythm and pitch, that is, between infrasonic frequencies and the audible frequencies of short-duration impulses.

While pulsar synthesis is not “granular” per se (using sampled audio), these concepts are fundamental to understanding granular possibilities regarding the time domain. By transposing rhythms into the audible frequency range, Stockhausen could build un-pitched noises from aperiodic sequences of impulses. He distinguishes twenty-one time octaves spanning the durations from 1/16th of a second to one hour, which constitute the range of perceivable events music composition.14

Roads builds upon and illustrates this theory in Microsound (Figure 21).

4.3 Trainlet Synthesis

Trainlet synthesis consists of a brief series (or train) of grains. It is based upon the basic principles of pulsar synthesis. However it uses grains of sound rather than electronic pulses. A train is described as the unit of musical organization on the time scale of notes and phrases. A train can last anywhere from a few hundred milliseconds to a minute or more.16

Figure 22 shows a single grain (d) followed by silence (s). The total duration is p = d + s, where p is the period, d is the duty cycle, and s is silent. Both p and d are continuously variable quantities. They are controlled by separate envelope curves that span a train of pulsars. Repetitions of the period form a train. They can be periodic or aperiodic, creating tones or noises. Trainlet synthesis generates rhythmically structured crossbred sampled sounds.

4.3.1 Trainlet Clouds

If grains all have a similar frequency, the result is a musical pitch—but as the frequencies of the grains are spread over a larger range, the result becomes a broad band noise, much like the natural textures of wind and water. These sounds create a remarkable sense of space and volume. Similarly, if the durations of the grains are all similar, the frequency spectrum and timbre of the resulting sound is much richer because of the phenomenon of amplitude modulation. In addition, when a short delay is placed between grains and then increased, the fused granular texture begins to "pull apart" as isolated events emerge perceptually from the texture and eventually establish rhythmic relations. Once global amplitude contours are added along with spatial deployment, we have replicated all of the basic acoustic properties of sound.

4.4 Glisson Synthesis

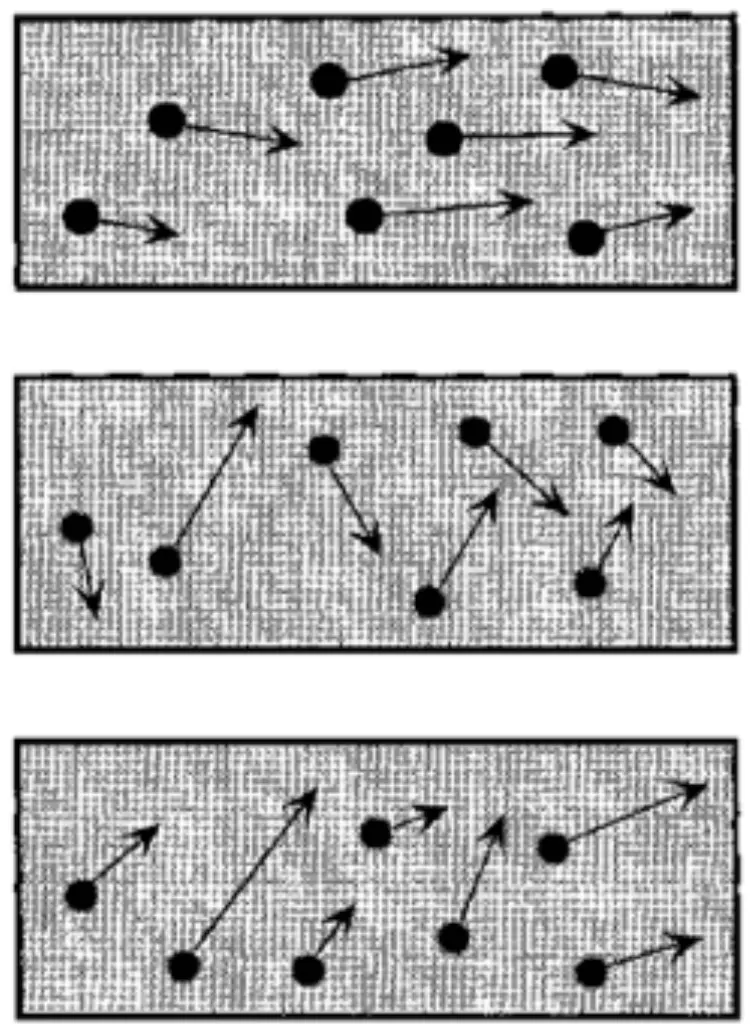

Glisson synthesis is a technique inspired by Xenakis describing each grain as a vector, rather than a point. Each individual particle has an independent frequency trajectory. Glisson synthesis scatters particles on the time-frequency plane, either synchronously or asynchronously bounded by time, frequency, and amplitude.

4.5 Spectral Grain Synthesis

Spectral grain synthesis is a method to manipulate timbre. It allows for the altering of formant regions through the addition of sinusoidal grains. The frequencies can also be manipulated, snapped or stretched from the harmonic series. This allows for pitched sounds to dissolve into noise.

Conclusion

Granular synthesis allows composers to to create textures unlike anything which exist in the past. Composers can now compose below the note level. It allows for the real time construction and deconstruction of sound, which can be a formal compositional element. The advent of computer technology has allowed for the manipulation of sound down to the microacoustic level. There is still a world of possibilities to be explored.

“ The basis of granular synthesis in the seemingly trivial grain has had a powerful effect on my way of thinking about sound. It clearly juxtaposes the micro and macro levels, as the richness of the latter lies in stark contrast to the insignificance of the former. Moreover, the range of densities obtainable, from the low levels associated with human gestures through those perceived as rapid and virtuosic, culminating with entirely fused textures, suggests a scale of composition ranging from human proportions to abstract. Finally, in terms of the theme of sound and structure, it is clear that the two are inseparable with this technique. The macro level structure is best described in terms of its component sounds, and the resulting sound complex is definable only in terms of the structural levels that characterize its organization. ”

— Barry Truax (1990) 8

“ It seems that a new type of musician is necessary, an ‘artist-conceptor’ of new, abstract, and free forms, tending towards complexities, and the towards generalizations on several levels of sound organization. The artist-conceptor would have to be knowledgable in such varied domains as mathematics, logic, physics, chemistry, biology, genetics, paleontology (for the evolutions of forms), the humanities and history; in short, a sort of universality, but on based upon, guided by and oriented toward forms and architectures. ”

— Iannis Xenakis (1985)

References

- Microsound by Curtis Roads (2001)

- Four Criteria of Electronic Music by Karlheinz Stockhausen (1971) youtube.com

- From Grains to Forms by Curtis Roads (2012) University of California, Santa Barbara, May 2012 cdmc.asso.fr

- The Evolution of Granular Synthesis: An Overview of Current Research by Curtis Roads (2006) Symposium on Legacies of Iannis Xenakis semanticscholar.org

- Creation of a Real-Time Granular Synthesis Instrument for Live Performance by T. T. Opie (2003) Queensland University of Technology qut.edu.au

- Time Shifting and Transposition with a Real-Time Granulation Technique by Barry Truax (1994) Computer Music Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 38-48 jstor.org/stable/3680442

- An Interview with Barry Truax by Toru Iwatake & B. Truax (1994) Computer Music Journal, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 17-24 jstor.org/stable/3681181

- Composing with Real-Time Granular Sound by Barry Truax (1990) Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 120-134 jstor.org/stable/833014

- Introduction to Granular Synthesis by Curtis Roads (1988) Computer Music Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 11-13 jstor.org/stable/3679937

- Real-Time Granular Synthesis with a Digital Signal Processor by Barry Truax (1988) Computer Music Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 14-26 jstor.org/stable/3679938

- Automated Granular Synthesis of Sound by Curtis Roads (1978) Computer Music Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 61-62 jstor.org/stable/3680222

- The Concept of Unity in Electronic Music by Karlheinz Stockhausen (1962) Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 1, No. 1., pp. 39-48 jstor.org/stable/832178

- Theory of Communication by Dennis Gabor (1943) Journal of the Institution Of Electrical Engineers, Vol. 9, No. 3. granularsynthesis.com