Table of Contents

Introduction

I began using scorewriter software about four years ago as I became fascinated with the idea that I could write anything down and have a group of musicians play it. At the time I did not know much about music, but using scorewriter software over the past few years has had a significant impact on how I read and hear music. I am very interested in how scorewriters affect the compositional process as I would consider myself to be of the “new generation” of composers born after 1975.6

My paper will be divided into two main sections. In the first section I will discuss how music technology of the Renaissance has shaped the world of music — specifically the invention of the printing press and the advent of music printing. In the second section I will discuss how the digital revolution is rapidly changing music in today’s world. I will focus my discussion on the invention of scorewriter software (such as Finale or Sibelius) and how it continues to influence composers of concert music. I will also touch on the idea that tablets and eBooks are replacing paper, and compare today’s online file sharing networks to Venetian trade routes. I will explain how these transformations have ultimately caused both the rise and fall of music publishing companies and how they continue to influence the way music is written, distributed, and performed in today’s world.

Invention of the printing press

The invention of the printing press proved to be a technological breakthrough that changed the world during the Renaissance. However, it is important to note that the printing press had been known throughout Asia for centuries before the technology spread to Europe. In 1439, German publisher, Johann Gutenberg, was the first person to bring printing to the European world. The printing press was first used to print music around 1470 for liturgical books with chant notation.13

The marketing and printing of music books began as a specialized industry and aimed at an elite audience, so publishing houses would often form partnerships to spread the risks among themselves. Many publishers would also seek alliances with members of intellectual circles in Venice. In fact, scholars have depicted the Venetian music printer as a colleague to the leading musicians and intellectuals of the time.2

The father of modern music printing

In 1501, Italian printer Ottaviano Petrucci changed the world of music forever when he created the first collection of polyphonic music using the printing press. The collection was entitled Harmonice Musices Odhecaton and it contained ninety-six polyphonic compositions written by composers such as Josquin des Prez, Heinrich Isaac, and Antoine Brumel.

Petrucci was very successful—in fact, he secured the first monopoly on music printing.10 Petrucci’s publishing house used the triple-impression printing method. This meant that each paper had to pass through the press three times: first for the staff lines, second for the text, and third to print the notes. Using this method, Petrucci became known for the beauty and precision of his elegant scores. His publications were deemed an artistic success, but the triple-impression method had some serious disadvantages as it was both time consuming and expensive.2 These flaws inspired other printers to experiment with different techniques and further perfect the craft of music printing.

In 1519, a man named John Rastell radically changed the music-printing industry forever as he implemented the single-impression method in his London publishing house. This process was much more efficient, as each page only had to pass through the press one time. French publisher Pierre Attaingnant was the first to take full advantage of the single-impression method to create a large scale commercial business in 1528. The single-impression method could print music faster, cheaper, and at higher volumes, however the pages tended to look much less elegant.10 Nonetheless, the music-printing industry entered a new era—moving away from the artisan stage and into the commercial period.

The birth of publishing companies

16th century Venice was known as the “marketplace of the world”.10 It proved to be the ideal location for the music printing industry to flourish due to its strong influence on the European economy and its community of culture-seeking residents. Between 1530 and 1560 more sheet music was printed in Venice than the rest of Europe combined10—clearly the industry of music printing was dominated by Venetian companies.

For the first time in history, sheet music could be sold as a commodity to the general public. Before this time printed music was a privilege only for use by upper-class intellectuals and church members.2 Most citizens saw an interest in the arts as a sign of sophistication because it took a great deal of both money and time to pursue artistic endeavors. The printing press stimulated a new market for music books and created a new competitive industry of music printing, distribution, and composition.

Effects of printing press on composers and styles

For the first time in history composers could have a reliable way to make a living. The advent of music printing provided two main opportunities for composers. First, they could become involved with a publishing house and market works of their own, selling books independently or through partnership. Second, they could accept books on a commission basis, selling their work to publishers, and taking much less of a financial risk.2 Similar to the publishers, composers would also seek entry into the inner circle of Venetian academies in hopes of attracting patrons.2 Whether it be independent sales, partnerships, or commissions—each of these ideas contributed to the complicated nature of economics in the 16th century music industry.

Although printed music began as a privilege reserved for the elite, once it became widely accessible due to printing technology, a new market of amateur musicians emerged. Once amateurs could purchase music to perform for their own entertainment, many new musical genres, styles, and forms arose. The growing preference for secular musical styles among amateurs led to the emergence of new vocal genres such as the Spanish villancico, the Italian frottola and madrigal, and the English lute song.3 The increase in diverse national styles was largely due to the fact that many amateurs preferred to sing in their own language. Although this occurred many years ago, these genres still have a great influence on music today.

The digital revolution

There is no doubt that computers have revolutionized the way we do many things—and music is no exception. The digital revolution has provided composers with many new opportunities—similar to what the printing press provided for European composers during the Renaissance. The world of music is rapidly changing due to computer technology—pencils are being replaced by MIDI keyboards, paper is being replaced by tablets and eBooks, publishing companies are being replaced due to scorewriter software, and libraries are being replaced by online file sharing networks. Douglas Engelbart, inventor of the computer mouse, describes the digital revolution as “far more significant than the invention of writing or even of printing”. He says that it offers the potential for humans to “learn new ways of thinking and organizing social structures”.4

Scorewriter Software

A scorewriter is a computer program used for editing and printing sheet music. Scorewriters were first introduced in the early 1990s and were quickly adopted by composers of concert music.6 They are essentially music’s version of Microsoft Word as they allow for simple editing, quick sharing of electronic documents, and create a clean, elegant layout. Scorewriters also include an array of compositional tools such as copy and paste, transpose, change key, change tempo, change meter, and even tools to develop motives such as inversion or retrograde. This technology is changing the way composers work as many of these tools help speed up tasks that used to be time consuming for composers, scribes, and publishers.

British rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes: “Technology gives us power, but it does not and cannot tell us how to use that power. We can instantly communicate across the world, but it still doesn't help us know what to say.”11 In other words, despite how we write down information, the human brain is still responsible for creating what is written.

Is computer technology having an effect on how composers write music? Can we directly trace the influence of scorewriters on composers of concert music?

Effects of scorewriters on composers

Francis Kayali from the University of Southern California was one of the first to research the effects of scorewriters on composers. His research suggests that yes, scorewriters have a significant influence on composers—but only those of the “new generation” born after 1975.6 Kayali found that most composers born before 1975 compose away from the computer and utilize scorewriters solely as an engraving tool. On the other hand, the majority of composers born after 1975 utilize scorewriters as a compositional tool. There is no doubt that scorewriters are becoming increasingly popular among young composers, but how much time is really saved by composing in a scorewriter?

In 2007, Chris Watson led a team from the University of New South Wales that conducted an experiment where professional composers were asked to perform composition and arrangement tasks under two conditions: using a pen and manuscript paper, and using music notation software. The goal of the study was to see how a composer’s behavior might change across the two environments, and whether or not their level of creativity is effected by the two conditions.

The study found that composers who write by hand spend 71.1% of their time writing notes and 24.98% of their time contemplating tasks. Composers who write using scorewriters spend 25% of their time typing in notes, 58% of their time accessing menus and tools, and 11.18% of their time contemplating tasks without entering notes or accessing menus.9

This research suggests that composers who use scorewriters spend less time engaging in pure thinking. The time consuming menus and tools within scorewriters have limited the composer’s ability to provide the maximum amount of detail. Composers who write by hand were more likely to provide more detailed notation.

The study concluded that while a great deal of time can be saved by a composer fluent with the software, it seems that any increase in productivity due to the speed of the software has been offset by time taken to audition competing musical options.9

Virtual instrument (playback) technology

In the past, composers have only been able to hear their orchestral works by playing them on a piano, or in some cases hire orchestras to hear a piece played in its entirety. Scorewriters offer composers the ability to playback notated music using synthesized virtual instruments. Playback technology can save composers time, money, and energy. Composers no longer need to be distracted from the “mentally strenuous”16 task of playing an instrument while composing. Because of this, composers can focus on purely compositional tasks. Although scorewriter playback will not contain the same nuances of a professional orchestra recording, it provides a decent replication to give the composer instant feedback on things like counterpoint, orchestration, and dynamics. One study has found that the repeated association of visual to sound can have great effects on learning music literacy.

While virtual instruments have many benefits, there are valid arguments that this technology is contributing to a decline in music literacy. Since scorewriters automatically follow music notation layout rules, musical illiterates might “get away with” mistakes that they are unaware of.16 Scorewriters may also be hindering creativity as the software generally makes composers more dependent on the standard Western notation system. Essentially, composers who rely on playback sounds will be less likely to think outside the box. Ben Bolter, Associate Director at Northwestern University’s Institute for New Music illustrates this phenomenon of illiteracy as he writes:

“ The ideal of the book will change: print will no longer define the organization and presentation of knowledge, as it has for the past five centuries...What will be lost is not literacy itself, but the literacy of print, for electronic technology offers us a new kind of book and new ways to write and read. The shift to computer will make writing more flexible, but it will also threaten the definitions of good writing and careful reading that have been fostered by the technique of printing. ”

Death of publishing companies

The advent of music printing in the 16th century created the need for three roles within each publishing house: publisher, printer, and bookseller—all of which have been replaced by computer technology.10 Scorewriters provide composers with the ability to easily create scores at a professional level. This has led many composers to ditch publishing companies all together and go down the road of self-publishing. The internet then allows for rapid sharing of music — eliminating the need for a publishing industry who caters only to the mainstream.16 American author, Clay Shirky, describes his concept of “mass amateurization” as he writes, “The future presented by the internet is the mass amateurization of publishing and a switch from 'Why publish this?' to 'Why not?'”12

In addition to scorewriters replacing the pen, printers are also being replaced by computer technology at a rapid rate in the form of eBooks and tablets. Many chamber ensembles are beginning to use computer screens instead of printed music. Musicians may prefer using an eBook over paper for a performance because of its ability to adjust screen brightness, contrast, the size of the notes, and of course store all their files digitally. Recent technology even allows for the ability to “turn the page” using a bluetooth foot pedal, so performers will never have to miss playing.

Even the way music is distributed has been affected by the internet. Booksellers and libraries are now being replaced by online file sharing networks. The most prominent example of a file sharing network in the music industry is The International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), also known as the Petrucci Music Library named after the beloved Ottaviano Petrucci. IMSLP seeks to “provide music scores free of charge to anyone who has internet access” and states that it “will always be freely accessible.” Over the past ten years IMSLP has collected over 350,000 scores and 40,000 recordings for over 110,000 works by over 14,000 composers. These scores are mostly scans of old musical editions out of copyright, however there are also many scores by contemporary composers who wish to share their music with the world by releasing it under a Creative Commons license.5

The next innovation to revolutionize music publishing will be the combination of scorewriters with the publishing technology itself. IMSLP has a vast repository of scores, though it only allows sheet music to be downloaded as a PDF document. The music publisher of the future will provide not only a visual for the sheet music, but also an interactive experience where music notation becomes interactive. Musicians will be able to listen to the piece as they view it. The software will follow along as you play, lighting the notes as they are played.

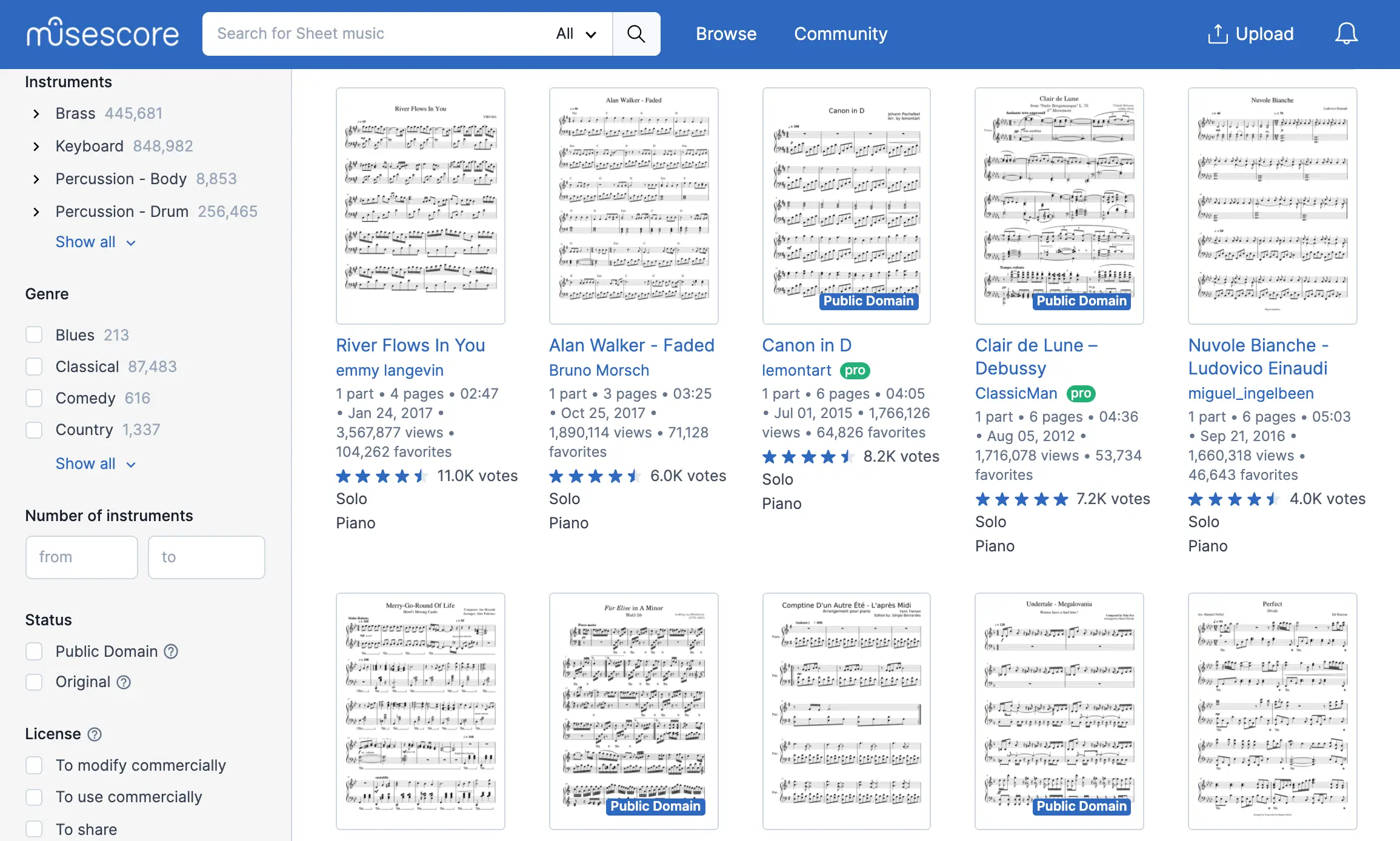

These transformations are already happening. Popular scorewriter software, MuseScore, has an online repository of scores where musicians can view and listen to sheet music online. This effectively eliminates the need for a publishing company all together.

The future of music technology

The advent of music printing made scores more accurate and accessible, increasing music literacy and standardizing music notation. It provided a way for musical ideas to be easily shared across the world. As a result, there was an emergence of new genres. This musical language is a gift from our ancestors—there is no doubt that we are and continue to be “heirs of the Renaissance”.3

In today’s world, computers continue to revolutionize the life around us. The advent of scorewriter technology has made an enormous impact on the the world of music, providing new opportunities for musicians — just as the printing press did in 16th-century Venice. I strongly believe that musicians should embrace new technologies because at this point, humans are only going to become more integrated with computer technology. In the words of American filmmaker, George Lucas: “The technology keeps moving forward, which makes it easier for the artists to tell their stories and paint the pictures they want.”1

Bibliography

- 1. American University. "Creativity and Innovation." Accessed November 22, 2016. american.edu.

- 2. Bernstein, Jane A. Music Printing in Renaissance Venice: The Scotto Press, 1539-1572. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. books.google.com.

- 3. Burkholder, J. Peter, Donald Jay. Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. A History of Western Music. 9th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014. wwnorton.com.

- 4. Dewar, James. "The Information Age and the Printing Press: Looking Backward to See Ahead." RAND corporation. 1998. Accessed November 20, 2016. rand.org.

- 5. "Goals." The International Music Score Library Project. Accessed November 21, 2016. imslp.org.

- 6. Kayali, Francis. "Music Notation Software: A Composer’s Best Enemy?" Resonance Interdisciplinary Music Journal, April 2009. Accessed November 6, 2016. University of Southern California. franciskayali.com.

- 7. Morris, Robert. "How Does Using Music Notation Software Affect Your Music?" New Music Box. August 1, 2002. Accessed November 6, 2016. newmusicbox.org.

- 8. Nardo, Rachel. "A New Role for Music Technology: Enhancing Literacy." General Music Today 22, no. 3 (April 17, 2009): 32-34. Accessed November 6, 2016. sagepub.com.

- 9. Peterson, John, and Emery Shubert. "Music Notation Software: Some Observations on Its Effects on Composer Creativity." The Inaugural International Conference on Music Communication Science 5, no. 7 (December 2007): 127-30. Accessed November 6, 2016. marcs.uws.edu.au.

- 10. Poore, Elizabeth M. "Ruling the Market: How Venice Dominated the Early Music Printing World." Musical Offerings 6, no. 1 (2015): 3. researchgate.net.

- 11. Sacks, Jonathan. "The Limits of Secularism and the Search for Meaning." ABC Religion & Ethics. May 17, 2012. Accessed November 22, 2016. abc.net.au.

- 12. Shirky, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York: Penguin Press, 2008. books.google.com.

- 13. Strayer, Hope R. "From Neumes to Notes: The Evolution of Music Notation." Musical Offerings 4, no. 1 (June 6, 2013). Accessed November 22, 2016. cedarville.edu.

- 14. Tejada, Jesús. "Hearing Music Notation through Music Score Software: Effects on Students’ Music Reading and Writing." International Journal of Learning 16, no. 6, 17-31. Accessed November 6, 2016. researchgate.net.

- 15. Thoreau, Henry David, and H. G. O. Blake. Thoreau's Complete Works. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1929. thoreau.library.ucsb.edu.

- 16. Watson, Chris. "The Effects of Music Notation Software on Compositional Practices and Outcomes." Victoria University of Wellington. 2006. ictoria.ac.nz.