Table of Contents

Abstract

I began experimenting with music notation software about eight years ago, as I became fascinated with the idea that I could write anything down and have a group of musicians play it. At the time I did not know much about music, my journey using music notation software over the past few years has had a significant impact on how I read and hear music. I am very interested in researching how medieval notation and neumes evolved into the modern notation system we use today.

This article will be divided into two main sections. In the first section, I will discuss the origins of western music notation—specifically the medieval music theory treatises of Hucbald of Saint-Amand (De harmonica institutione) and Guido d’Arezzo (Micrologus). In the second section I will discuss how the lasting impact of these treatises are relevant today. I also am intrigued by the pedological aspects that arose from the treatises of Hucbald and Guido d’Arezzo.

Hucbald of St-Amand

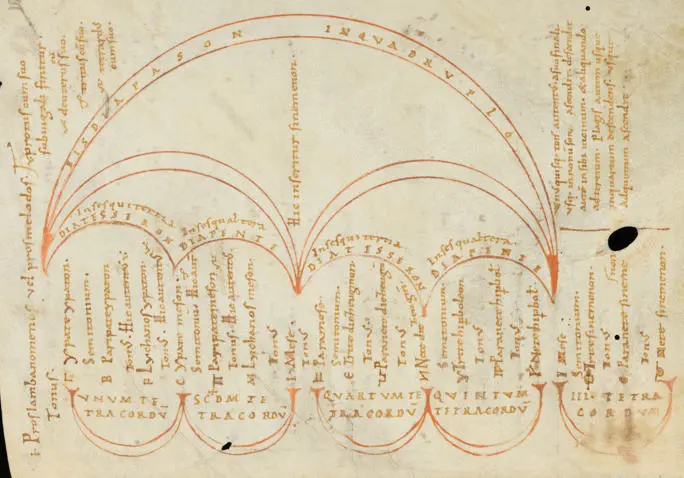

Hucbald of St-Amand (840 - 930) was a Benedictine monk who wrote the first definitive work on western music theory: De harmonica institutione (c. 870). It is known to be the earliest account of a scale system, which reorganized the entire pitch system in an attempt to reconcile Frankish practice with the ancient Greek theory.5

Before Hucbald’s treatise, Boethius’s De institutione musica (c. 500) was the most comprehensive music theory guide available in the Middle Ages. Inspired by Boethius, Hucbald wrote his own treatise which created the nomenclature required to, for the first time, realize Boethius’s theories.3 In his treatise, Hucbald presented the idea of the semitone (semitonium) and the whole tone (tonus). He stated that these are the basic constituents or “elements” that make up all the scales.2 Hucbald created a new system which codified what was only aurally known during the time.

The Harmonic Institution

De harmonica institutione was a music theory guide aimed at musicians. Topics included psalmody, pedagogy, and notation of chant. It established a system for defining the pitches and scales used in plainchant repertory.6 Hucbald assumed the reader’s knowledge of Gregorian chant and used examples from the repertory in his aurally based pedagogical method. He defined a pitch-specific scale system based on sixteen pitches, along with letter notation for the transcription of chant melodies.2 De harmonica institutione does not use numerical interval ratios nor monochord division. Instead, scales and the intervals that they are constructed from, are explained through plainchant melodies and intonation formulas of the cantus tradition.

Theory of Scales

Hucbald describes the musical note as the fundamental basis for any scalar system. Individual, discretely pitched notes are combined to create melodies. Hucbald backs this concept with the authority of the ancient ars musica.11 Hucbald goes on using his scale system to describe the ways which melodies relate to the modes at two important points: their endings, and their beginnings.2 He describes an equal relationship between the finals and the notes four or five steps below. Hucbald writes that each final has “a certain union of connection” to the note five steps higher such that most melodies are found to end in them as if by rule.11

Hucbald describes the modum scalarum—scales that ascend and descend like a flight of stairs, each set apart from the other by the quantity of their proper interval (proprii spatii quantitate discreta).11 This very early use of the “scale” analogy and the reference to determinate intervallic positions demonstrates Hucbald's extrodinary capcity for innovation and his ability to formulate new theories about the universe. Hucbald of St-Amand made a great impact on both music theory and music education by laying the foundation for our western music notation system.

Guido of Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo (991 - 1031) was a medieval music scholar known to be the inventor of modern musical notation. As one of the most influential music theorists and pedagogues of the Middle Ages, he revolutionized the music education methods of his time.12 His innovations spanned across areas such as the hexachord system, solmization syllables, and the music staff notation which replaced neumatic notation. A monk of the Abbey of Pomposa, Guido moved to Arezzo, and presented the Pope with the results of his research on notation and teaching: Micrologus (c. 1028).

Micrologus

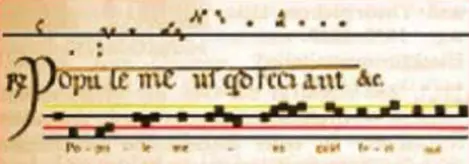

In Micrologus, Guido laid the foundation for our modern western musical staff. He created a system consisting of four lines positioned a third apart — as it remains today in modern music notation. Guido writes: “pitches are so arranged that each sound, howsoever much it is repeated in a chant, is always found in one and the same row...thus, however many sounds there are on one line or on one space, they all sound similarly”.14 This was the birth of musical clefs. Clefs could now be used to indicate what note a given staff line represents.

Guido’s staff was made up of two colored lines: the yellow line was C, a the red line was F. Neumes were placed above or below these lines, providing a pitch center for the neumes. Before Guido’s staff concept, music notation was limited to “diastematic neumatic notation” where neumes were centered around an imaginary line which represented a given pitch. Guido provided a definite way to see the distance from the note center.

Guido’s music notation system provided students and teachers with a way to visualize music. It allowed musicians to use the placement of the neumes in comparison to the lines to determine the exact intervals between notes.12 The combination of elements presented in Micrologus resulted in a more efficient way to teach, learn, and read music. Guido believed that his innovations would “perhaps briefly and adequately open the door of the art of music” to students.15 He created an easier, simpler, and more efficient way to learn music.

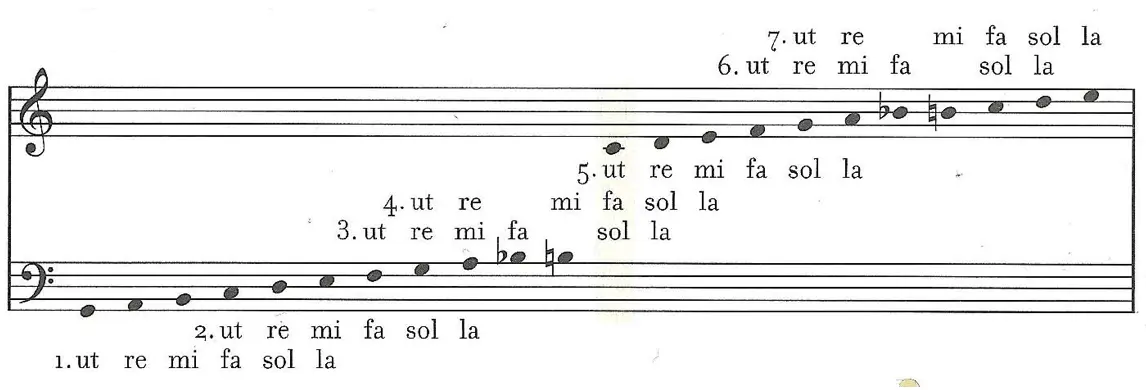

Solemnization

Solemnization is a method for sight singing where certain notes are assigned to specific syllables. Guido’s syllables of solmization were: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la. Today we use the syllables do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, and ti. With the solmization syllables, singers could become familiar “with the intervallic context surrounding each syllable” within the hexachord.8 While Guido’s hexachord system was simply a codification of previous theories, the solmization system was a new invention.12 Guido realized the connections between the hexachord system and solmization syllables into a single pedagogical system. Guido came upon his solemnization concept when he realized that the first six phrases of the chant Ut queant laxis outlined the six church modes. He noticed that the first syllable of each phrase of this chant could be used to identify mode. This was the beginning of what we now know as solfege.

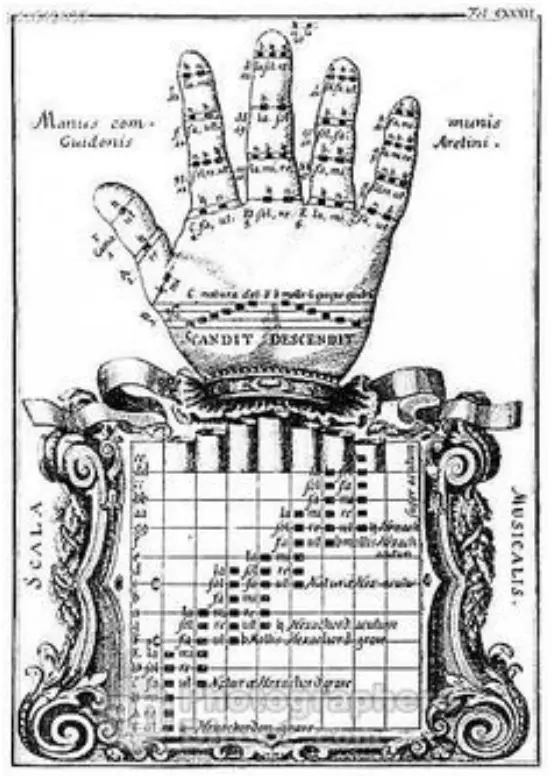

Guidonian hand

The Guidonian hand is both a mnemonic and a pedagogical device based on Guido’s solemnization syllables. The association of a clef and its syllables with a specific place on the hand helped memory and provided teachers and students with a simple method of practicing the scales and intervals.1 Although named after Guido, the precise origin of the hand is unknown and is not mentioned in any of his writings. It is believed that the Guidonian hand was conceptualized after Guido’s time, however it is a pedagogical device based entirely on his studies.

Personal Reflection

While today’s western music notation system may seem far removed from that of Guido and very far removed from that of Hucbald, their ideas continue to play an important role in Western music to this day. Every new musical idea is built upon music of the past. This is clear to see when analyzing history and the progression of musical complexity.

Leonard Bernstein’s idea of “musical monogenesis” suggests that the evolution of musical complexity is preordained by the harmonic series. The earliest music was monophonic, using only the fundamental. As time went on, music began to be harmonized with fourths and fifths—then thirds and sixths. As our ancestors discoved more about the universe, their music grew in chromaticism and harmonic complexity.

It is interesting how the notation system seems to follow this same trajectory. Music notation began with no lines, then two lines representing tonic/dominant, and now we use six lines. Over time as music gets more complex, its notation must also get more complex. The western music notation system was improved upon to keep up with the discovery and implementations of both harmonic and rhythmic complexities.

Evolution of Notation

Notation innovations were not only a product of new musical ideas, but also a product of new means of distribution. The advent of music printing caused scores to become more accurate and accessible, leading to better music literacy, and more standardized notation practices. The next innovation will likely be developed utilizing the new world of functionality provided by tablets. It seems the future of music notation will be transformed by this technology — the digital revolution is rapidly changing music in today’s world.

Maybe the next major innovation in notation will be displaying rhythms on a moving time scale. We already see this in various digital audio workstations, although it has yet to be implemented into mainstream notation or educational practice. I strongly believe that musicians should embrace new technologies because at this point, humans are only going to become more integrated with computer technology.

Guido’s Legacy

Although Guido’s hexachord system has become obsolete, his solmization syllables remain an essential element of modern music education. He laid the foundation for modern music solfege. Solfege gained popularity and became wide-spread in the mid-twentieth century through the methods of Zoltán Kodály, whose system is based upon Guido’s theories.

I think Guido was onto something with his concept of using colors to aid music notation. Although it never truly reached wide-spread use, color could literally add another dimension to the music notation system. I believe that colors will be used in the future not only for music notation but also for music education.

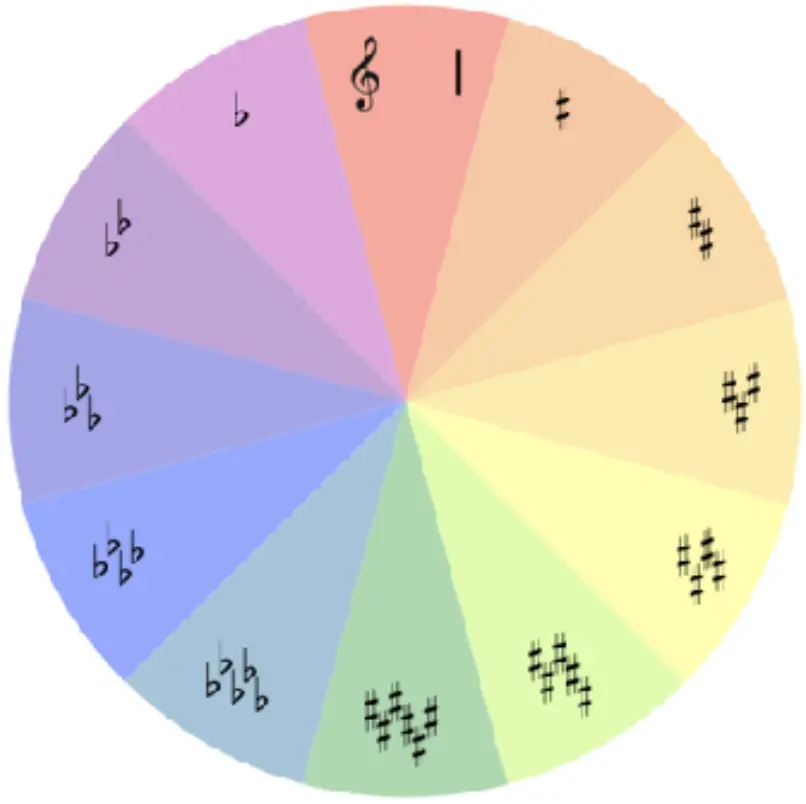

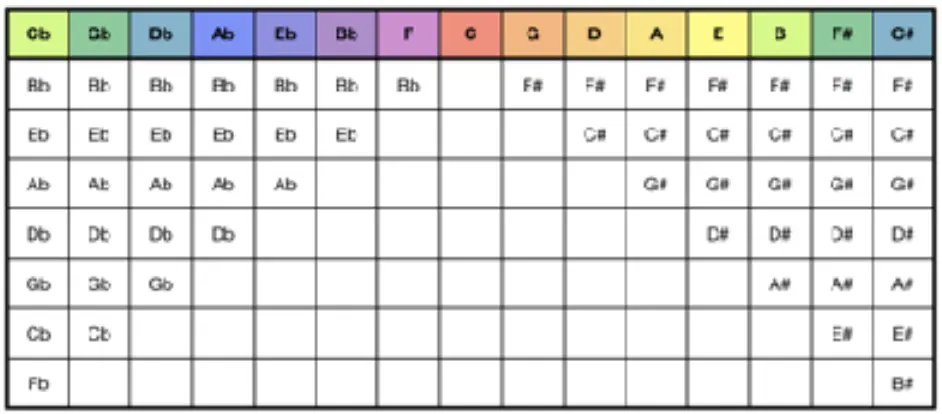

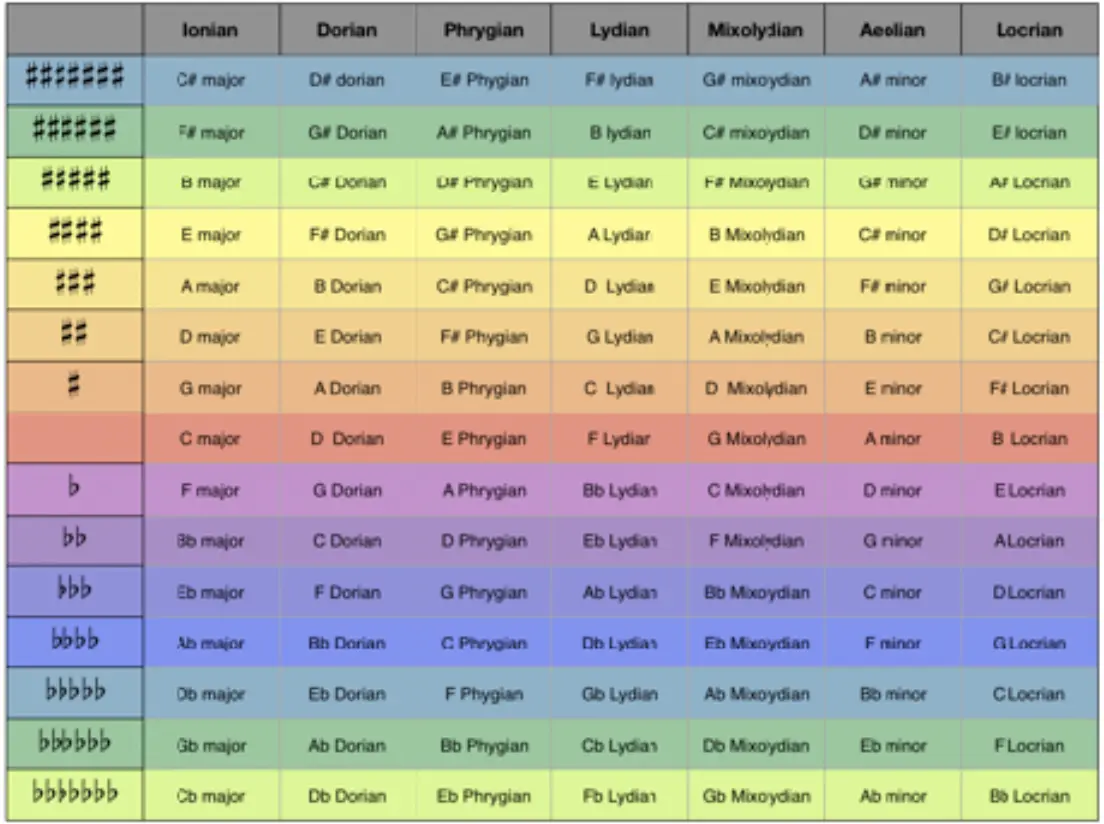

In my own personal reseatch, I have created serveral diagrams that utilize color to represent key relationships. My thought was that related keys can be expressed as similar colors, and distant keys can be shown as contrasting colors. I was inspired when I learned about Guido’s theories of color.

I believe that the only reason Guido's colored system was never adopted is due to the complexity it would create for the printing process. However with tablets, this will no longer be an issue. These diagrams are currently printed on a piece of paper, however they could be utilized even more effectively. This color system could be utilized in a virtual space where colors are not fixed to C. They could modulate with the modulations in the music, where red always reflects the current key center. I have recently been learning how to code and plan to develop these concepts into an interactive educational tool.

Bibliography

- 1. Berger, Carol. “The Hand and the Art of Memory,” Musica Disciplina 35 (1981): 12, jstor.org.

- 2. Cohen, David. “Notes, scales, and modes in the earlier Middle Ages.” The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory (2002): 307-357. cambridge.org

- 3. Cope, David. Hidden Structure: Music Analysis Using Computers. Wisconsin: A-R Editions, 2009. ucpress.edu.

- 4. Fuller, Sarah. “Interpreting Hucbald on Mode.” Journal of Music Theory 52.1 (2008): 13-40. Accessed October, 25 2018. dukeupress.edu.

- 5. "Hucbald of St Amand." Grove Music Online. Accessed October, 25 2018, oxfordmusiconline.com

- 6. Latham Alison. “Hucbald of Saint-Amand.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press, 2011. oxfordmusiconline.com.

- 7. Leach, Mark. “A Practical Supplement to Guido of Arezzo's Pedagogical Method.” The Journal of Musicology 8.1 (1990): 82-101. Accessed October, 25 2018. ucpress.edu.

- 8. Mengozzi, Stefano. The Renaissance Reform of Medieval Music Theory: Guido of Arezzo. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1. cambridge.org

- 9. Mengozzi, Stefano. “Clefless Notation, Counterpoint and the fa-Degree.” Early Music 36.1 (2008): 51-64. Accessed October, 25 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/em/cam137. academic.oup.com

- 10. Miller, Samuel. “Guido d'Arezzo: Medieval Musician and Educator.” Journal of Research in Music Education 21.3 (1973): 239-245. Accessed October, 25 2018. sagepub.com.

- 11. Palisca, Claude V. Hucbald, Guido, and John on Music: Three Medieval Treatises. Yale University Press, 1978. cambridge.org.

- 12. Reisenweaver, Anna. “Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning.” Musical Offerings 3.1 (2012): 37-55. Accessed October, 25 2018. cedarville.edu.

- 13. Szendrei, Janka. “The Introduction of Staff Notation into Middle Europe.” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 28 (1986): 303-319. Accessed October, 25 2018. jstor.org.

- 14. Guido of Arezzo. Prologus in antiphonarium. indiana.edu.

- 15. Guido of Arezzo. Epistola ad michahelem. books.google.com.

- 16. Nash, Lexie. "Guido d’Arezzo’s Notes". Wordpress.com, 2016. nashgazette.wordpress.com.